In the report Money and Debt of the Scientific Council for Government Policy (WRR), the introduction of a full reserve bank and the discussion of public interests in payment transactions remain too abstract in nature. This is a missed opportunity.

In het kort

– The WRR analysis on the full reserve bank and public interests in payment systems needs to be made more concrete.

– Full reserve payment accounts are already offered abroad and different models are readily available for the Netherlands .

– It is up to politicians to choose the implementation option and the degree of government involvement.

The financial crisis has shown that, in the banking sector, payment transactions, debt and money creation are closely intertwined. The concern that payment transactions would come to a standstill ‘forced’ politicians to intervene at large banks. Since then, the public awareness has grown that it is of great importance to reduce or undo this interdependence.

One of the ideas was to revisit older financial models, similar to those of the Wisselbank in Amsterdam at the time (Lelieveldt, 2017b). The core idea was that the customer’s money would be placed in safe government hands, and would not be lent to third parties. In this way, a full-reserve payment account is created. However, the realisation of this, through the initiative with the name of ‘Depositobank’, encountered problems with regulations in the Netherlands (Buitink and Van der Linde, 2019).

Similar reforms in the money system – proposed earlier in history – were investigated by Van Dixhoorn (2013) on behalf of the Sustainable Finance Lab. This was followed by a call to safeguard the payment system as an essential public infrastructure and to create a ‘Depositobank’ (Van Tilburg and Weyzig, 2013). Thanks to the efforts of the citizens’ initiative Our Money (Ons geld), this resulted in a petition to the government about money creation, followed by the report Money and Debt (Geld en Schuld) of the Scientific Council for Government Policy (WRR, 2019). It also discusses the obstacles to setting up the full reserve bank.

The WRR report contains an extensive and very readable sketch of the financial history and of the problems surrounding money creation. However, as far as payments are concerned, the analysis remains too superficial and too abstract. For example, there is a lack of insight into the development of the institutional frameworks, and the notion is lacking that since 2001, public interests have increasingly been embedded by European legislation (Box 1).

Box 1 – European embedding of the public dimension in payment services

Since the introduction of the euro, public interests in payment transactions have been increasingly anchored by European rules. That is what it is all about:

– European regulations in the field of payment transactions, which lay down requirements that determine a minimum level of performance and limit the liability of the customer;

– the Maatschappelijk Overleg Betalingsverkeer (MOB) (Social Consultation on Payment Transactions), supported by DNB, in which demanders and providers of payment solutions discuss topical and urgent issues with each other;

– the actual agreement made in this MOB to ensure that there will be sufficient cash withdrawal and deposit facilities in the Netherlands;

– a European Retail Payments Board set up in Europe, following the example of the Dutch MOB, with a similar aim of putting on the agenda and discussing socially relevant themes;

– the obligation to use the same price per transaction in euros for domestic and foreign payments;

– the statutory maximum standards for the pricing of card payments to retailers;

– the legal obligation for local authorities to run their bond management through the treasury;

– the legal obligation for banks to make basic payment accounts available at reasonable cost to all residents of Europe and to ensure rapid switching to other banks;

– Europe’s legal obligation for providers to open their systems to competitors with PSD2 (Payment Services Directives 2);

– The legal obligation in the Netherlands for providers of back office settlement systems to meet certain standards of continuity and operational reliability.

The WRR does not sufficiently investigate in detail what the alternative implementation models could be for a full reserve bank. It also misses the opportunity to raise the question of whether the ideas on services of general economic interest, in addition to existing rules, could be used to safeguard public interests further (De Bijl et al., 2006).

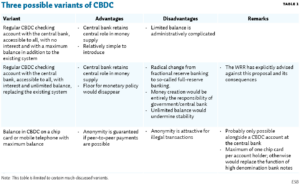

In this article I further detail the analysis of the WRR and explore the various ways in which a full reserve bank can be set up. There are three feasible options that differ in the degree of government involvement.

The custody function is public, not the bank’s.

The core of the idea of the full reserve bank is that the public has the possibility to deposit its money in such a way that it is not further lent to private parties. The concept of a public payment bank reminds us of the former Postgiro: the state-owned organisation that was in public hands and offered safe payment accounts. This association is understandable, but analytically incorrect. What we are looking for is not necessarily a public organisation, but an organisation that offers the public the service of a full reserve payment account.

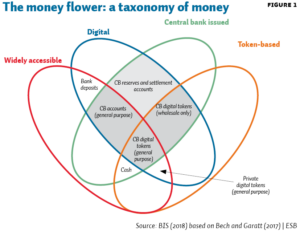

One of the models is to store the money at the central bank. This creates a ‘full reserve’ payment account. By payment account I mean a cash registration of money that, when a payment is made, can be mutated remotely. From a technical point of view, this is possible in a central accounting system, the payment account, but there is nothing to prevent an implementation in which part (or all) of that money is in the form of digital currency. The payment account with central bank money is therefore, when offered by a central bank itself, the same as central bank digital currency (CBDC). But such a payment account with money deposited at the central bank can of course also be offered by a private party. So, when I discuss the (full reserve) payment account below, the conclusions will also be directly relevant to the appearance of digital currency.

Options

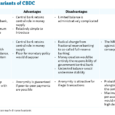

The WRR mentions different models for offering full reserve payment accounts. They refer to a central bank and another institution, a ‘payment bank’. In particular, this concept of ‘payment bank’ can be further specified on the basis of the following parties in the market: a government organisation, a party with an (opt-in) banking licence, a payment institution or an electronic money institution.

Central bank

The central bank is the first model. In practice, until the end of the 1990s, the central bank offered full reserve payment accounts to account holders. This changed with the formation of the European Monetary Institute and the European System of Central Banks (ESCB). Article 2 of the ESCB Statute required central banks to act in accordance with the principle of an open market economy with free competition (EU, 2016). Therefore, De Nederlandsche Bank (DNB) limited access to its account facilities only to account holders with a specific status as a government or financial institution. As a result, DNB’s full reserve payment account disappeared from the market after many years.

The legal and analytical considerations of those days are still relevant today. As a direct provider of full reserve payment accounts or as a publisher of CBDC, the central bank does not come into play. However, the central bank can still facilitate the safe custody of customer funds via account holders who do have access to the account system (Koning, 2018).

An individual bank can set up a payment account, and hold the deposited funds safely at the central bank. In Norway, for example, the Safe Deposit Bank of Norway does this for a small group of account holders (SDBN, 2016). From an economic point of view, the model is based on the willingness of shareholders to bear the (start-up) losses. However, the level of the bank’s absolute costs is relatively limited for a wealthy large shareholder, and may well outweigh the benefits of the safe storage of money.

Government organization

A second model is that a full reserve account is offered by a government organisation. An example of this is in England, where the old Post Office Savings Bank still exists, but now as the National Savings and Investments (NS&I). The NS&I is both an independent governing body and an executive part of the Treasury. The public can save with that institution, and the savings are covered by the government. The actual back office has been fully outsourced to the French IT company ATOS/Worldline, which has a significant role in payment transactions. Although NS&I does not currently offer accounts with payment functionalities, this can quickly be organised commercially.

In the Netherlands, it is obvious to look at a possible role for the Treasurer-General of the department of Finance. In fact, in the wake of the financial crisis, the Treasury has tightened its monetary grip by obliging local authorities to keep an account with the treasury. This is known as ‘treasury banking’, and it is precisely for the management of that treasury that the Treasurer has his own account with the Dutch Central Bank. The Treasurer could also use this access to store third party funds and offer full reserve payment accounts.

Bank

A third model is that a party with a banking licence decides to create a full reserve payment account. The WRR discusses in its report that this can be made to work by the bank because a bank ringfences the relevant payment balances within the bank and has them safely stored at the central bank. This is similar to the Norwegian model discussed earlier. In addition, it is conceivable that a bank may specialise in this area. A Dutch example is Bunq.

In terms of exposures, Bunq almost achieves the ideal of full reserve payment accounts. Both in the forum of Bunq and in the conditions and communication to the account holders, it appears that Bunq holds the money of customers fully with the European Central Bank and that the deposit guarantee is applicable.

However, due to the interpretation of the European Banking Authority (2014) regarding the definition of a bank, DNB requires that part of the bank’s capital be invested in the market. Indeed, Bunq invests part of its own funds in bonds. In addition, Bunq has recently made it possible for customers to choose for themselves whether to invest the funds in the market. In essence, this makes it a full-reserve bank in which the client can decide for himself to what extent he wants to become part of the debt system in society.

The model in which a regular bank transforms itself into a full-reserve bank therefore seems workable, but has one disadvantage. Such a bank is subject to the deposit guarantee scheme, which is not necessary but does entail obligations and costs. A full reserve bank without a deposit guarantee scheme is therefore not possible under the regular banking licence (Buitink and Van der Linde, 2019).

The only appropriate banking licence model would be that of the local voluntary opt-in banking licence, in which funds are attracted from the public but not invested. The banking licence, however, does not allow direct access to the central banking system for safeguarding the funds. The party with this licence must therefore obtain such access via a government institution or a regular bank. This will have a cost-increasing effect, irrespective of whether the latter parties are authorised and inclined to do so.

Electronic money institution or payment institution

Electronic money institutions and payment institutions could be useful operating vehicles, because they are obliged to use a foundation to shield customer funds from the financial flow from their own business operations, and because they are not subject to the obligations concerning the deposit guarantee (Bodifée, 2019). Under the Settlement Finality Directive, however, they are not allowed to deposit the customer funds in the central bank’s Target2 system. This gap in the regulations is remarkable, since both the Consumer and Market Authority (ACM, 2017) and the government (Kabinet, 2012) are of the opinion that this possibility should be offered and that the directive should be amended. It remains to be seen, however, whether this will happen soon in Europe.

For the time being, the road to the full reserve bank via the electronic money institution seems to be deadlocked, at least in the Netherlands. In Lithuania, however, the central bank offers electronic money institutions the possibility of depositing these funds in the Target2 system.

Customers who hold an account with a licensed institution in Lithuania therefore have exactly the account that the founders of the full reserve bank are aiming for: full reserve, deposited with the State, and free of deposit guarantee fees. People who want to set up a full reserve bank can therefore do so in Lithuania or seek cooperation with a party that is currently active there. With a licence in Lithuania, they can also do business in the rest of the euro area.

The Lithuanian exception exists because the central bank has also been the owner of the clearing house for mutual payment transactions there for many years. As the owner of the clearing house, they provide – neatly within the European framework – payment institutions and electronic money institutions with access to the central banking system via the Centrolink clearing system (Bank of Lithuania, 2015).

It is common practice for all participants in such a clearing arrangement to have a collateral account with the central bank to cover unforeseen risks in the execution of payment transactions. What is happening in Lithuania is that participants are also allowed to open an additional collateral account for customers’ funds. This has the additional advantage that the funds are not subject to the bankruptcy of these banking parties themselves. This clearing arrangement is one of the reasons for Lithuania’s popularity as a location for new payment and electronic money institutions.

Services of general economic interest

There are legitimate social considerations to propose full reserve payment account from the point of view of the public interest. However, due to the various legal barriers, full reserve payment accounts are costly and the enthusiasm is low. For example, despite extensive media coverage, only some 2,500 founders at the full reserve bank were prepared to pay around 60 euros a year. A profitable private activity may therefore hard to achieve with the full reserve bank. It is also uncertain – although I am positive about this – whether there will always be large-business shareholders who will want to finance a Norwegian model with continuous loss-making. Thus, the question remains if government has possibilities to safeguard the public interest by ensuring the provision of full reserve payment accounts.

The European framework on public service obligations may offer a solution. It is a framework that aims to offer all kinds of services that are deemed to be ‘state aid proof’ in the public interest. This includes, for example, the contract that the State concluded in 2007 with the Terschelling Steam Boat Company and the municipality of Terschelling. Since it is in the public interest that a permanent ferry service exists, especially in the unprofitable low season, this service is designated as a service of general economic interest. The State will ensure that the service remains available by tendering out to an entrepreneur. Numerous implementation variants and regulations are important in this respect (MinBZK, 2014).

The application of this framework to financial services is well described by De Bijl et al (2006). They detail what a public service obligation for payment transactions could look like in terms of the minimum content of the service, its availability and affordability. The actual provision of such a service to the market can be guaranteed by designating one specific bank as a service provider, designating all banks, holding an auction, or by leaving it to the market. The choice of the final model should be based on a targeted cost-benefit analysis, appropriate to the specific service and market demand.

In the Netherlands, three de facto general interest obligations have already been defined in the payment sector. First of all, a consensus agreement has been made for the availability of payment services in the National Forum on the Payment Systems, so that withdrawing and depositing money remains sufficiently accessible. Secondly, the large processors in the payment system have statutory minimum requirements to guarantee continuity. And thirdly, we see that the availability of affordable payment accounts is regulated by a European directive. This last issue in particular could better have been achieved using the framework for services of general interest, but this did not happen for political reasons (Lelieveldt, 2013).

Of course, designating a fourth public service obligation in the payment system is also an option. If the commercial set-up of a full reserve bank would be unprofitable, but politicians attach great importance to it, why not define the full reserve payment account as a service of general economic interest?

The real question is therefore, which variant of the full reserve payment account is politically preferable. There are, of course, ideological preferences as to the desired role of the market and the government. But it is obvious to consider other relevant issues as well. Examples include the declining use of cash, the strategic dependence of government on its main banker and the confidentiality of personal data in the digital payment system.

The full reserve bank: three options

A publicly organised variant would come down to extending the role of the Treasurer-General. In addition to the current treasury banking, the Treasury could offer full reserve accounts to the public. This role can be expanded further, so that the Treasurer also has a role to play in solving bottlenecks in the acceptance of cash by the local government and in the efficient cash processing for specific businesses (those who are rejected by the bank as cash customers). The expertise that is built up may also lead to the government becoming strategically less dependent on the current main banker that executes the government payment transactions.

A publicly enforced, but privately executed solution consists of defining the provision of full reserve payment accounts as a service of general economic interest that is performed by one or more private players. The previous analysis shows that that organisation would then either be licensed as a payment or electronic money institution or obtain an opt-in banking license, so that the Deposit Guarantee Scheme does not apply. It is conceivable that the tender for the service also includes the requirement that any leakage of personal data from third parties in the application of PSD2 rules should be prevented. In this way, part of the private sector is encouraged and rewarded if it adapts its product proposition to the desired degree of confidentiality and robustness in the payment system.

Finally, there is the market-driven option in which politicians do not intervene. In this model, the Depositobank initiative itself could, as a private payment or electronic money institution, operate in and from Lithuania and serve not just the local market, but also the rest of Europe. This might make the full reserve payment account available on a scale and with a functionality that does make it viable. And perhaps the threat of this foreign option will help our national regulator and central bank reconsider the obstacles they have so far suggested that exist with respect to the deposit banking model in the Netherlands (Lelieveldt, 2017a).

In sum, the full reserve bank is up for grabs – any takers around ?

References

ACM (2017) Fintechs in het betalingsverkeer: het risico van uitsluiting. Rapport Autoriteit Consument & Markt, December 19.

Bank of Lithuania (2015) Operating rules of the payment system Centrolink of the Bank of Lithuania. Article at www.lb.lt.

Buitink, P. en R. van der Linde (2019) De econoom aan zet voor bankrekening zonder kredietrisico. ESB, 104(4769), 21–23.

Bijl, P.W.J. de, E.E.C. van Damme, S. Janssen en P. Larouche (2006) Universal service in banking. TILEC-rapport, 14 March. Available at pure.uvt.nl.

Bodifée, H.J. (2009) Kaarttransacties temidden van de betaaldiensten. Tijdschrift voor Financieel Recht, 9 (September), 325–331.

Dixhoorn, C. van (2013) Full reserve banking: an analysis of four monetary reform plans, april-juni. Article at sustainablefinancelab.nl.

EU (2016) Geconsolideerde versie van het Verdrag betreffende de werking van de Europese Unie: Protocol (nr 4.) betreffende de statuten van het Europees stelsel van centrale banken en van de Europese Centrale Bank. Document 12016E/PRO/04 available at eur-lex.europa.eu.

European Banking Authority (2014) Report to the European Commission on the perimeter of credit institutions established in the Member States. EBA-rapport, 27 November.

Kabinet (2012) Kabinetsreactie op het groenboek over betalingsverkeer ‘Naar een geïntegreerde Europese markt voor kaart-, internet- en mobiele betalingen’, 7 March. Available at www.parlementairemonitor.nl.

Koning, J.P. (2018) The narrow bank, blogpost, 7 September. Available at jpkoning.blogspot.com.

Lelieveldt, S. (2013) Directive on payment accounts: the wrong road to universal services in banking, guestblog, 18 June. Available at guests.blogactiv.eu.

Lelieveldt, S. (2017a) DNB onnodig streng. Het Financieele Dagblad, 29 July.

Lelieveldt, S. (2017b) Betalingsverkeer: hoe markt en regelgeving elkaar maken en breken. ESB, 102(4753S), 7–11.

MinBZK (2014) Handreiking diensten van algemeen economisch belang, juli. Ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninkrijksrelaties. Available at europadecentraal.nl.

SDBN (2016) Annual report 2016. Safe Deposit Bank of Norway. Available at www.sdbn.com.

Tilburg, R. van, en F. Weyzig (2013) Achtergrondnotitie bij de inbreng voor de Commissie Structuur Nederlandse Banken van leden van het Sustainable Finance Lab, 25 February. Available at sustainablefinancelab.nl.

WRR (2019) Geld en schuld: de publieke rol van banken. WRR-report, 100.